IN THE DOLLHOUSE

Written By: Vamika Sinha

Explore the double-edged power of photography: a medium that captures, alters, and sometimes invents our very memories

What makes photography such a seductive medium is its promise of perfection?. Imagine, at the cusp of its invention: the gateway to freezing a moment for, effectively, ever. The meaning of the word “memory” shifting out of its clothes into something more permanent. With our phones, photography also ushers in the irreal, morphs the meaning into something weirder and more god-like. Now the camera can change the memory, make it smoother or shinier or take the unsmiling person out from the back. The procedure at the heart of Michel Gondry’s Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) sputters amazingly into action with a few clicks and swipes. I can erase you. I can forget you. You were never here.

Elaborate sets get constructed, then the sleek, crafty edits in post – the fantasy can get ever more hairsprayed like a bouffant reaching greater heights. It’s here, where the image passes through the seams into fiction, that things get playful, even radical. Conceptual photographers mix narrative storytelling, artifice and performance into their work to build alternate worlds that might mirror, distort or completely depart from the IRL. When the artist is a woman, especially, the use of fantasy and make-believe can take on a knife edge, exaggerating the absurdity of what is actually real. Gender roles, cultural expectations, burdens borne – the curving limits of a woman’s body are all shown up. Look at how these very real things controling us and our movements, our freedoms… look at how unreal they are. Take this absurd, made up picture and see how ridiculous your vision is, how abnormal the lens taken for the norm.

It’s speculative fiction. Some change up the rules of the dollhouse; some cut up their own image; some muddle expectations and subvert the punchline; others create fantastical havens, sanctuaries, third, fourth, fifth, sixth spaces. Last year’s biggest cinematic hit Barbie, directed by Greta Gerwig, conjured up a perilously plastic Barbieland to show us the real wasteland we don’t question enough. If Eliot’s titular poem laments the aftermath of a catastrophic war, Gerwig’s movie, however rosy and happy and hopeful, cautions us to the harsh contours of a dollhouse we still live in by rote.

DINA GOLDSTEIN

Canadian artist and photographer Dina Goldstein began her career as a photojournalist, foraying into staged photography in 2007. Her first such series was Fallen Princesses (2007-2009) which critiqued the sunset- hued, picture book “happily ever after” tropes offered by Disney stories and the like, in which princesses aspired to men and marriage as their highest ideals. We know now that times have shuffled a bit forward: Disney princesses are more headstrong, their princes less consequential, their bildungsromans more robust. But 17 years ago, Goldstein, already an avid feminist, became a new mother realizing her daughter would inherit stories binding her in a corset of outdated, limited imaginations for her own life. (Jia Tolentino writes brilliantly on this phenomenon of how young girls depicted in literature impact the aborted arcs of girlhood in her book Trick Mirror).

Fallen Princesses ups the surrealism of the Disney princess by dousing her in grim daily life. Snow White must deal with being a housewife to a lothario husband and four tiny kids.

Cinderella sits with local drunks in a bar, thousand-yard staring into the liquid. Rapunzel falls sick – cancer – and holds her own blond braid in her hands like an aftershock. In this series, princesses become ordinary women, yet their individual heroisms are only more pronounced.

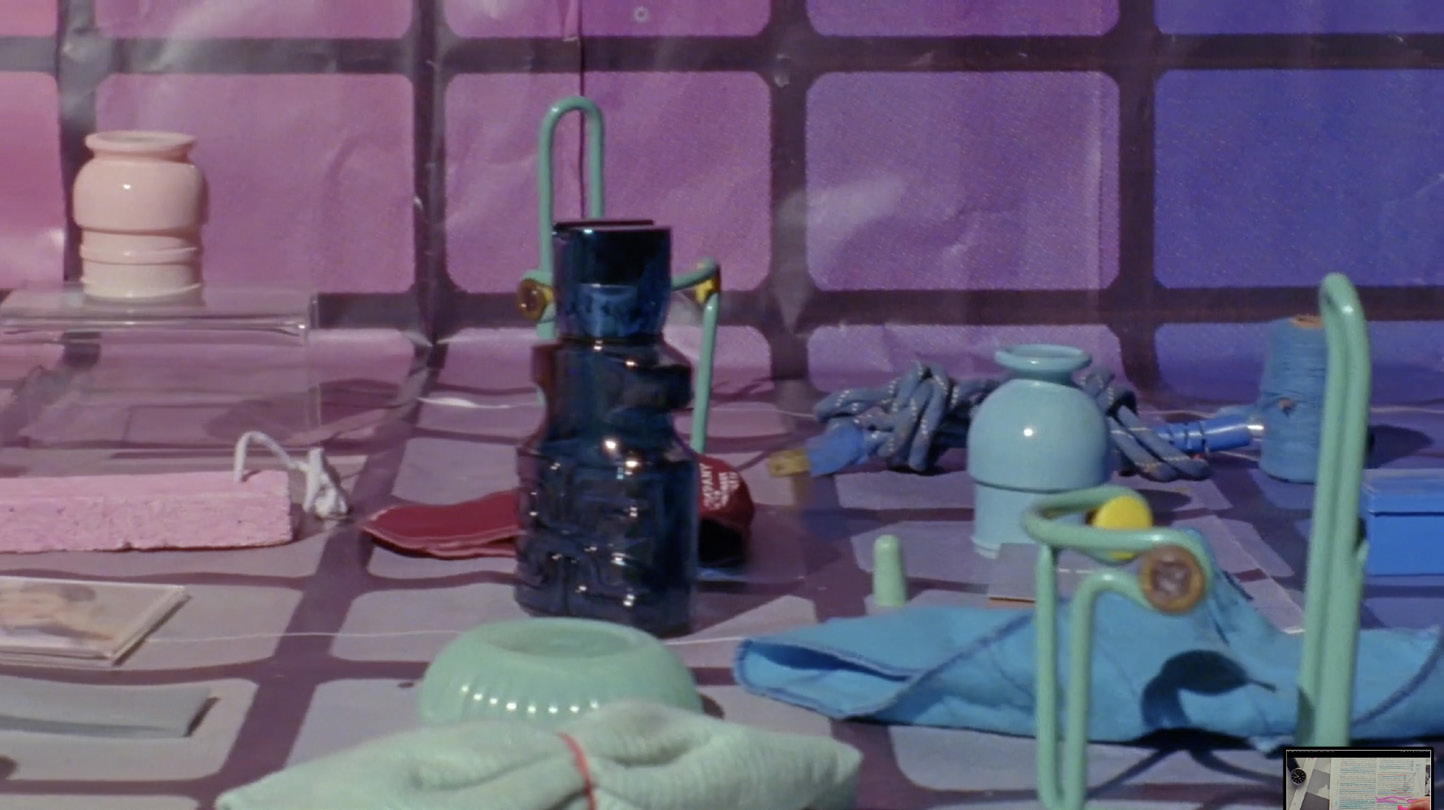

In the Dollhouse (2012) came a few years later, a 10 part sequential narrative unfurling like a death-pink comic strip. It’s the darker ancestor of Gerwig’s film. In Goldstein’s version, Barbie and Ken live in their sickly pink dreamhouse, a metaphor for the sticky death traps of marriage. They’re like plastic insects drowning in a great ventriloquist’s honey trap – the puppeteer may be God or Man, patriarchy, gender, heteronormativity. Anything rigid and hegemonic, if you think about it. Ken cries at night, reading magazines with Barbie in bed. He wears painful stilettos and has an affair with another man. Barbie passes out alone at the dinner table, suffers what seems to be an extended psychological breakdown. In one shot, “Haircut”, she takes scissors to all her hair, wearing a man’s suit. The Musee d’Orsay infamously requested the image to be included in its 2013 Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera catalogue. In the final image of the series, Barbie literally loses her head. Many of us remember decapitating her body, not realizing, then, what we were also learning to do to ourselves.

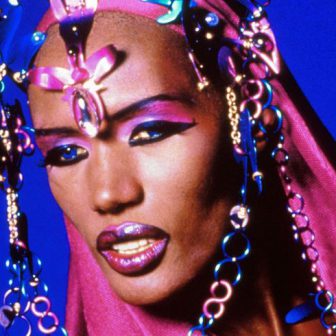

JOHN YUYI

Taiwanese photographer John Yuyi’s instagram bio is “Pet”. She recently shot the cover story for Olivia Rodrigo in Rolling Stone, promoting the young singer’s sophomore album Guts. At first glance, the cover looks like a regular glam image of a girl putting on lipstick. Then you notice the giant lipstick tubes in the background with Rodrigo’s face copied onto each of the mounds of pigment. In another shot of the editorial, Rodrigo’s long straight hair seems to stretch out into an infinite thread, streaming out the jaws of a hot straightener. The hair clips on her head are exaggeratedly big, like bunny years. Rodrigo’s Barbie- like frame is shrunk into the large expanse of a white room, making her hair become a tether to something beyond

the frame – a different reality? Normalcy? A wire to a charging port?

Yuyi’s work doesn’t just dabble with the surreal or uncanny, with commentaries on tech and cyberfeminism. It fuses them together. She herself began her career online, posting oddball shots of herself covered in temporary tattoos, emojis, and stickers. These stickers themselves contain images of bodies, often her own. When imposed onto her, she manipulates the image of her body with more images of her body, making herself a curious site of excess not to be deplored or criticized or sexualized, but simply demanding a double take. In one work, she prints her made up face onto the packaging of a pot of instant noodles. In another, she prints artful nude self-portraits onto cigarettes – Yuyi cup noodle and Yuyi cigarettes. How can the world make you an object for purchase before you’ve done it yourself?

SARA CWYNAR

When Sara Cwynar was asked to create a custom bag design for Dior, its sunny runny egg-yellow version opened up to reveal a Ghibli-blue sky with white clouds inside – a bag of dreams.

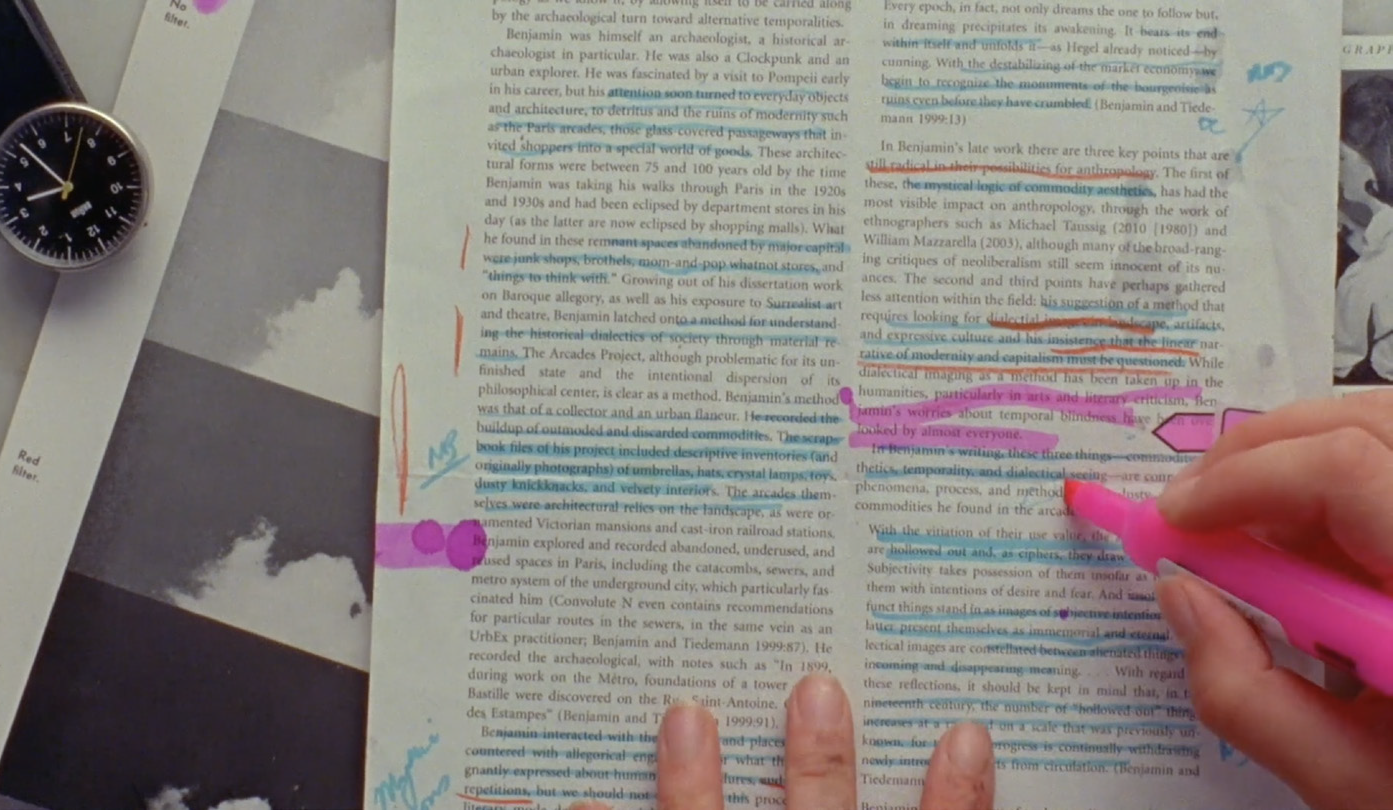

Cwynar is known for her multidisciplinary work

spanning photography, film, and installations. She folds

in multiple sources of theory to discuss issues many

of their theorists could not have fathomed – visual oversaturation, cellphones, swiping, ubercapitalism, the online manipulation of female bodies. Cwynar’s work, simultaneously, is beautiful for the very excess it critiques; her works are digital marvels of cuts and edits and cleverly costumed footage. The grain of her film looks as soft and porous as skin, as virginal as an unedited image. There are stacks and piles and rows of objects and curios, a nod to the artist’s interest in archiving while mimicking the spoils of a supermarket. Cwynar’s imagery shows us the complexity of living with so much choice – how beautiful to have so much, yet how unbearably unwieldy to live with it.

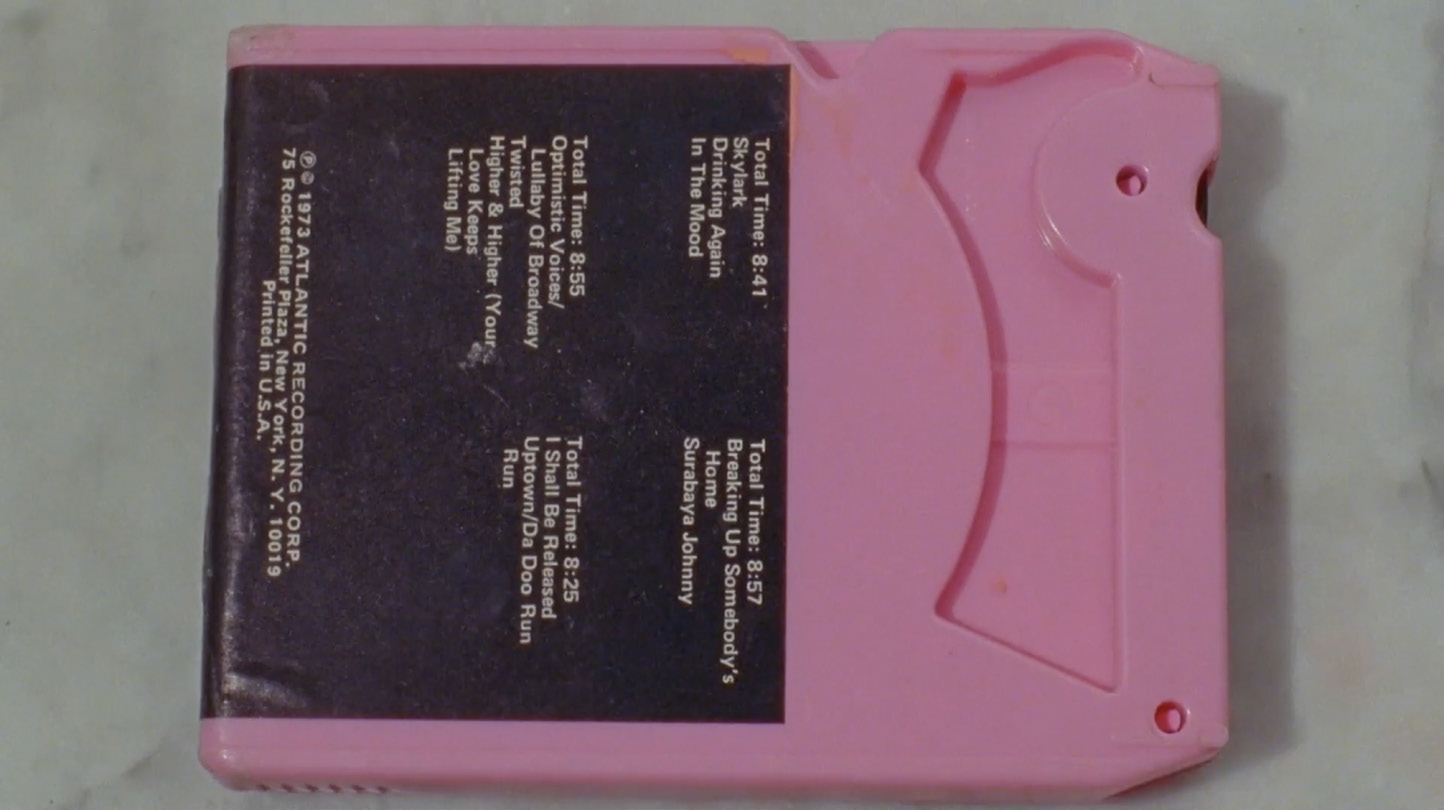

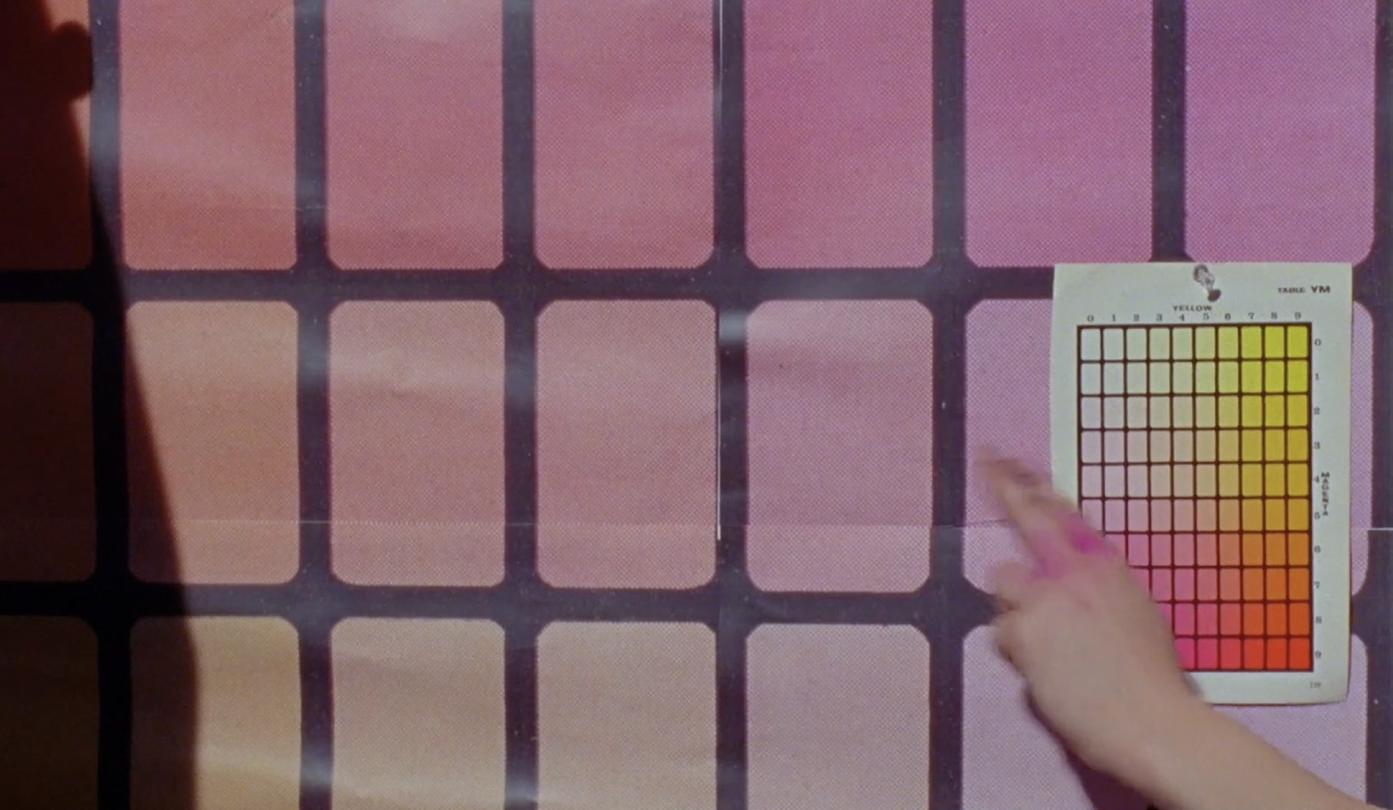

Rose Gold, which was first exhibited in Brooklyn in 2017, is a short film named after the most popular iPhone color. A male and a female voiceover tumble in and out of each other – his as clipped as Siri, hers slightly pensive– offering meditations on consumerism, the desire for objects, American history, Heidegger, color theory, and purchasing power. “People understand more if you communicate through things bought and sold.” “When you buy something, you lose the power to buy something.” She ponders a brand of purportedly unbreakable plastic kitchenware from the fifties, a new American phenomenon, which fades and shatters with time. Eyeshadow and blush palettes fill the screen. A cracked iPhone against a rose pink rotary phone. A cheek pulled upwards, turning slightly red. The erratic rhythms of the images in and out and on top of each other form the aisles of the Internet. Yet all of it is appealing, delectably staged and coordinated by color, like biting into pastries. Consumption is so sweet, after all.

The fixation with color theory is a larger theme in Cwynar’s practice, perhaps the reflection of it being a crutch, as a categorizing tool in an endless whirligig of choice. If we unlock the color, we can understand new things. Rose gold looks most beautiful on all skin tones; rose gold epitomizes an Apple-y peak of capitalism. Rose gold is not harsh, it’s feminine. Who decides all of that? Cwynar presents color as a curious arranging grammar for a world increasingly incomprehensible.