INTRODUCING: BLACK MIRROR’S BILAL HASNA

Written By: William Buckley

For Sorbet, issue #46, we sat down with actor Bilal Hasna to talk absolutely everything – his recent role in the latest series of acclaimed dystopian show, Black Mirror, his turn as the titular Layla in Amrou Al-Kadhi's queer club-kid romance, his Palestinian/Pakistani heritage, and carving his way in the world.

WILLIAM BUCKELY: Bilal, let’s start from the beginning. How did you get into acting?

BILAL HASNA: I come from a family of storytellers. Culturally on both sides, South Asian and Arab, there’s always been a big emphasis on passing down stories, whether it’s family stories or just fables that have been overheard. Stories would be shared at the dinner table: my grandad would have you in the palm of his hand, my grandma too, my dad is an amazing storyteller, and my mom is incredible at impressions. Telling stories has always been a big part of my upbringing and all of my cousins are artists too, even though my parents and aunts and uncles weren’t, because didn’t have the opportunity to be. But they raised us with stories and I became obsessed. So I did the classic Saturday school, performing arts thing.

WB: What kind of stories would they tell? Things about their day?

BH: Sometimes, but mostly things that happened in childhood, in their past or from history. We hung out a lot as an extended family growing up, so there was always something to share, especially from my granddad. The way he would command a room, I always thought that he should go on The Ellen DeGeneres Show. He would have gone viral.

WB: I read that you went to Cambridge to study English literature. So you didn’t go down the route of a drama school like Guildhall. Why was that? What was your plan?

BH: At the time, I was really into English literature and I wanted to be an academic, like a lecturer. But I went to an audition on whim because a slot randomly popped-up and I liked the look of the play — the role was for a very masculine Sicilian American dad. It’s really weird how your life hinges on these moments, but I don’t think I’d be an actor if I hadn’t have gone for that. I just found the play interesting, but it was a very different role. I got the part, it went well, and I got the bug. Then I did loads of plays at Cambridge. We went to the Edinburgh Fringe twice and we took Shakespeare’s Othello around high schools in Europe, the opportunities were crazy.

Sorbet Magazine

Bilal wears flowers embellished

cardigan, fitted cowboy L/S shirt,

washed workwear denim pants,

LV Ride P.FR Blue U sunglasses,

LOUIS VUITTON

Sorbet Magazine

WB: After all of those experiences, when you left uni, you had an agent and they were putting you forward for auditions and all of the rest of it. Then you got into writing too, you wrote a play called “For a Palestinian”

BH: That was about a year after I graduated. I left uni in June of 2020, so I graduated in the pandemic. And then I worked for a childcare charity for a year that I used to go to, called The Winch in Camden. It was down the road from where I grew up. They had a new wing of their charity that was working with social housing residents in North Camden. So I worked there and in that same year, I did my first professional gig, which was a BBC short film called Shahid’s First Shave. It was a 15-minute short film about a Pakistani-British teenager who grows loads of facial hair in the summer and he’s not really allowed to cut it off, which he feels insecure about. It’s about growing up as a brown boy in the UK, basically, and it’s really sweet.

Sorbet Magazine

Bilal wears oversized DB coat, washed workwear denim pants, LV rider suede boots, LOUIS VUITTON

Sorbet Magazine

Bilal wears oversized DB coat,

washed

workwear denim pants, LV rider suede

boots, LOUIS VUITTON

Sorbet Magazine

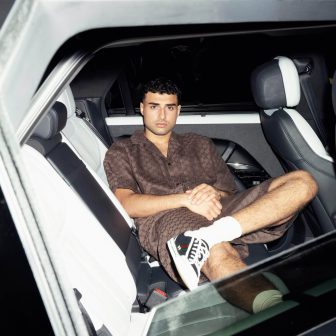

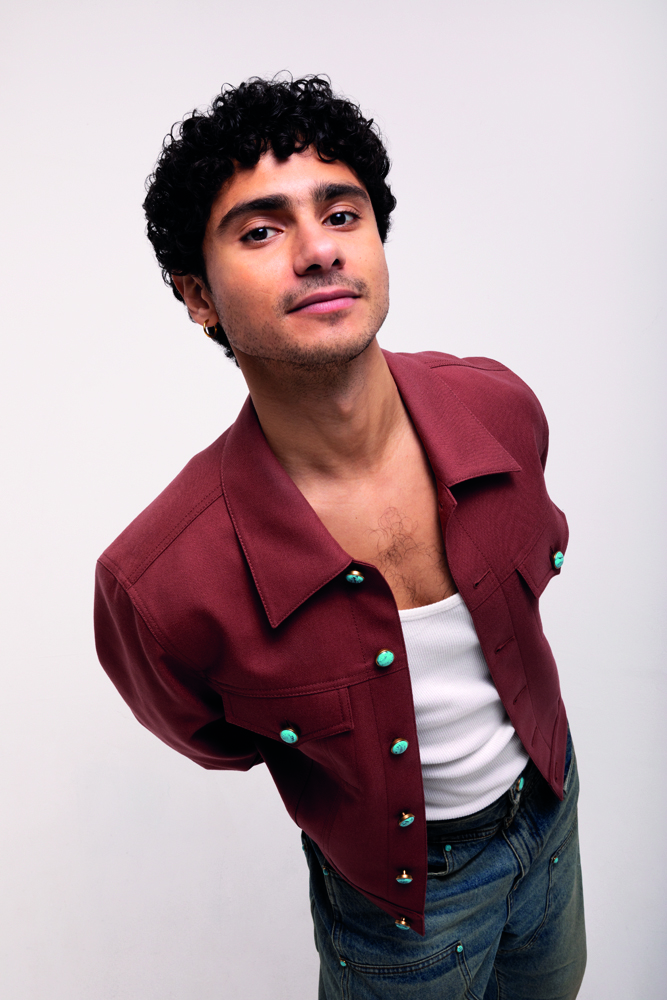

Bilal wears chic

collarless jacket,

tank top,

washed workwear

denim pants,

LOUIS VUITTON

Sorbet Magazine

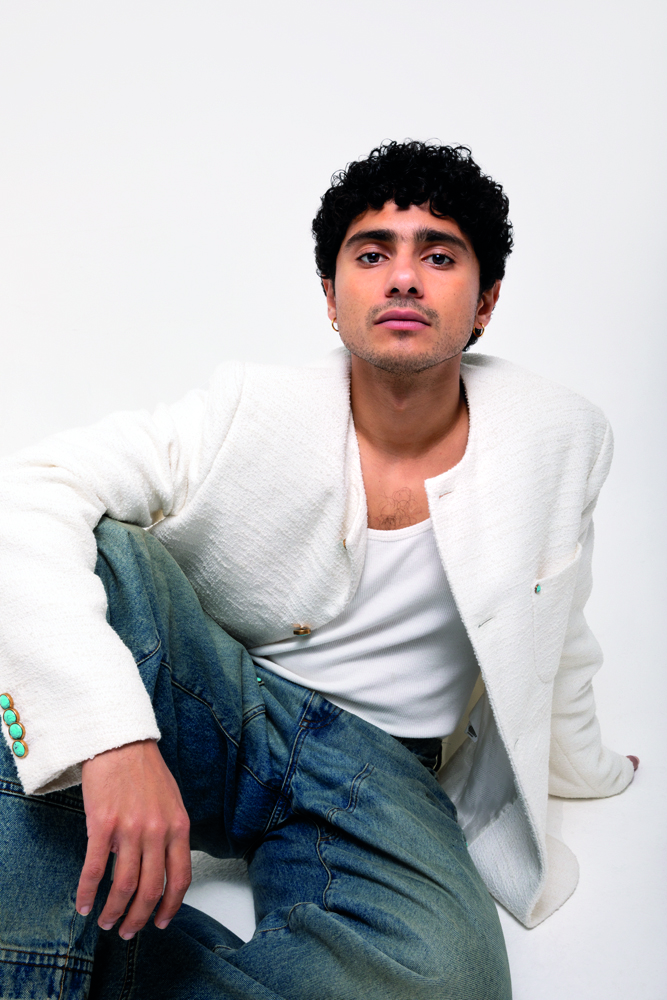

Bilal wears Damoflage cowboy SB jacket, Damoflage tailored cowboy flared pants, LV Rider suede boots, LOUIS VUITTON

Then I didn’t work again for another 10 months before I got a role on a prison drama called Screw. It was only about four weeks of filming, but it gave me enough money to leave the charity job and pursue acting full-time. When I had more time on my hands, the self-tape for Extraordinary came through. So it was all very serendipitous. At the same time as this, we did For a Palestinian the first time round, which me and my housemate and long-term collaborator, Aaron Kelejioglu, had been working on for about a year. We did the first work in progress performances just before Extraordinary Season 1 started filming. So that started a different chapter in my life, where I was more of a full-time professional actor and writer too.

WB: You mentioned Extraordinary, was that a big break? Did you find you were getting more invitations to audition or more roles after that?

BH: It was a big turning point. It was one of the lead characters in a big-scale comedy series for Disney+. I’d never been to a readthrough before for show. In Screw, I was number 52 on the call sheet and suddenly I was number three. In every episode, filming all the time, there’s a lot of pressure that you put on yourself because it is your first big break. And you never know if it’s going to come again, so you want to make sure that you’re doing it right. I did notice that after getting Extraordinary, suddenly auditions were for higher-profile roles, for main roles and supporting roles, not just a scene or two.

WB: How did Layla come about? Which I saw, by the way, you were so incredible. BH: I appreciate that, that’s sweet. I was actually going through security at Gatwick Airport because I was flying to Palestine to go see my family and the self-tape email came through for the feature film debut Layla. And so I did the self-tape in the West Bank in Ramallah. I knew of Amru’s work before. I’d followed them for a while. And so I knew I wanted to be in this film. It was a crazy audition process, like eight or nine rounds across three months and they put me in drag. I went out to buy clothes that I thought the character would dress in. I’d never done drag before, so I think they wanted to see that I could do it. But of course, I was familiar with that feeling of diva worship and I’ve always been obsessed with all the big female divas, from Etta James to Whitney to Amy Winehouse. That obsession is often what leads to drag because you want to participate in that somehow. That’s a feeling I know very well, I’ve spent a lot of time lip syncing in my bedroom.

WB: Same. How was the drag? Can you now get yourself into drag now? Did you develop those skills?

BH: So Adele Firth was the makeup designer, she created all of the looks. And there was a woman called Anna Moreno, who was in charge of the wigs. It was amazing because the unit base for Layla was just this school in Bethnal Green. I think it was abandoned or it was in the holidays, but the science lab was just full of wigs and makeup. You’d come in the morning at 5am and the they were already backcombing a wigs. Then there was a guy called Guy Common, who is a drag artist in their own right under the name of Titus Grone, who did my makeup, applied it every day. And they are incredible. And actually, they’ve been my makeup artist recently by pure coincidence on a TV show I just finished filming recently. So we were in the chair every day chatting away. But on my own, I can do the base layer, not shading or contouring or anything like that.

WB: When you were reading the script, with Pakistani and Palestinian heritage and the sort of taboos that still exist with religion and conservativeness, were you worried about broaching the subject matter that’s quite controversial? And the sex scenes, how did that all sit with you? And what was your thought process for tackling something so groundbreaking?

BH: Obviously the film is a deeply vulnerable and exposing project. It involved a lot of nudity and sex and it also discussed things that are quite sensitive, like the relationship between Islam and queerness. But I think the reason I wanted to do the role was because I felt like I could really identify with the way in which the film articulates the joy and compatibility of possessing these identities and that actually being Muslim and being queer, they are not two mutually destructive categories. We’ve always existed and we always will. We’ve always got one foot back in history and one foot in the present. Especially now in our current context, there are certain political agendas that like to weaponize the existence of homophobia in certain countries to justify occupying those countries or bombing those countries or in the case of Israel and Gaza, committing a genocide in those countries. In November last year, there was a photo of an Israeli soldier in a totally decimated part of Gaza with a pride flag and it said, in the name of love on it. As if bombing a town to smithereens and denying all HIV medication from entering Gaza is going to help any queer Palestinian. But I think it’s so important for Amru themselves, as a queer Arab as well, to tell their stories. I think once they start telling their stories, it’s quite clear the ways in which their identities have been weaponized when you see what the actual reality is.

Sorbet Magazine

Bilal wears embroidered cowboy L/S shirt, fitted cowboy L/S shirt, MNG Rodeo tailored cowboy bootcut pants, LOUIS VUITTON

Sorbet Magazine

Bilal wears tailored trucker jacket, underpinning tank top, washed workwear denim pants, LOUIS VUITTON

WB: With Layla, like you say, that visibility just seems so important, because people don’t know and they’re fed what they’re told to believe. For one reason or another, they don’t have the capacity to objectively think outside of what they’ve been told. Did that go through your mind when you were reading Layla? Has that always been something that you wanted to do, to shine that light to raise the awareness to tell those stories?

BH: I didn’t do Layla because of what it stood for symbolically. I’m just looking to play characters that I feel are real and I can see in their totality. With Layla, I could really see that person. And I think it just so happened that that person contained an identity that has been weaponized and generalized, that has been rendered totally reductive in its status in the discourse. And actually, a lot of that identity intersects with me and so I could understand what the film was trying to do in the bigger sense. But the reason I took the film was because the character just felt very real to me. From the fact that it’s really Layla that runs away from their own family. It’s much easier for Layla to compartmentalize that this is my family who are a bit traditional, but not really. And this is my queer life in London and I’m going to separate those two things. I’m never going to invite my family round. These are two separate worlds. And Layla can’t really compute how maybe they might be part of the same world. And so Layla decides to separate them. It’s not the family that does and that felt quite interesting because I feel like it’s normally it’s always the family that’s going and beating the queer kid up and the queer kid has to run away in this big trauma narrative. I’m sure that’s true for many people, but also, and just as validly, you have many queer Arabs who have internalized their own estrangement, because they think that’s the easiest way to deal with what the world has told them are two very different things. That’s one of the reasons why I thought it was very interesting as a script. It was the same For a Palestinian, I didn’t write that story to set out to, it wasn’t a corrective project. It wasn’t a Guardian article or whatever. It was because there was a man called Wael Zaida, who I found fascinating. And he represented something that I feel like I’ve seen in so many Palestinian men that I know, this romantic spirit, this intellectual sensibility that is so often lost when we talk about Palestinian men. But the thing that drew me to him was just his life. The priority is always the life itself, the totality of the life. Same with Layla, you want to just do that justice. And if you do that, then it can say all sorts of things.

WB: Which it did. It raised so many discussion points on so many levels. And what has the reaction been like since for people that have seen it?

BH: Very positive. And it’s done really well in the cinemas. Independent films really struggle and it’s been in the cinemas at the same time as Wicked and Gladiator. And to be honest, more than any project of mine, so many people in my life have seen it. I keep getting messages from people who’ve gone to watch it. More people will see Extraordinary than Layla, probably but it feels like a bigger event somehow. I think because there’s something about the grandeur of it being in the cinema, because you have to go and watch it somewhere. I mean, my face obviously is like on the poster and that’s kind of crazy. I feel very blessed and supported, it’s a nice way to end the year.

WB: Tell me, you said you were working on something else that the makeup artist was. What have you got coming up? What are you excited about?

BH: The Agency is the name of that show and we’ve just wrapped, but it’s already come out. It’s a Showtime and Paramount show that was really fun. My scenes are with like, Michael Fassbender and Richard Gere, it’s crazy. Then there’s this Lord of the Rings anime film that I’m in, that’s coming in the new year. Then there’s all sorts of bits and bobs like I did a bit on Black Mirror. And there’s a film called A Christmas Karma with Eva Longoria. It’s like a musical adaptation of A Christmas Carol, which will come out next Christmas 2025.

WB: Exciting. Finally, I have to ask, what is your favorite flavor of sorbet?

BH: Mango.

CREATIVE CONCEPT STUDIO SORBET | PHOTOGRAPHER JEMIMA MARRIOTT | CREATIVE DIRECTION WILLIAM BUCKLEY | PRODUCTION ASSISTANT KHANSAA HOULBI | GROOMING CHARLIE CULLENT AT FORWARD ARTIST | PHOTOGRAPHER ASSISTANT | LEE FURNIVAL | TALENT BILAL HASNA | FASHION LOUIS VUITTON MEN FALL-WINTER 2025 | CITY LONDON

Related Photoshoot, Fashion

- Fashion

- 5 Min Read

PACKING, EN POINTE: RIMOWA INTRODUCES THE BALLERINA PINK ESSENTIAL SUITCASE

January 27, 2026