A red sky at night is the sailor’s delight, but a red tide delights no one. A red door in China is considered auspicious, but the red planet is ruled by the God of War. How is it that the color red can hold so much meaning for so many societies? Is it because red represents all the human vitals, both physiological and experiential? Clearly, there is something fundamental, something unique to the longest perceivable wavelength on our visible spectrum. In ancient times red and violet — the color with the shortest wavelength — were cousins under the moniker ‘purple’. What a royal family they made, red and violet, what with all their lovely kin (see: scarlet, carmine, incarnadine, and cerise). No wonder it is tempting to write about red by waxing a little purple; it would be treasonous to desaturate a topic so vivid. Embrace the blush! Bask in the glow of its therapeutic hue! If necessary, assign it a district unto itself, but shun it not. Red is the color of life.

MONA HATOUM: HOT SPOT (2006)

ROBERT INDIANA: LOVE (1965), LOVE (1966), LOVE (1967), GENERAL IDEA: AIDS (1987)

Oh, Robert Indiana. For someone who had so much love to give — his most notable works are surprisingly sentimental — he didn’t get much back. A major figure in 20th century American art, Indiana rubbed shoulders with the likes of Andy Warhol, Ellsworth Kelly, and other cultural elites of the post-war New York scene. His word and symbol pieces from the late 1950s and early 1960s put him at the leading edge of the burgeoning Pop Art movement.LUCIO FONTANA: THE RED PAINTINGS FROM HIS SERIES I TAGLI – SLASHES (1958–1968)

The slash says it all: brave new world. At least that is the promise Lucio Fontana — the Argentinian-Italian artist famous for rupturing the sacrosanct surface of the Modernist canvas — believed it held. Holes of any shape and size represented for Fontana not a violation, but the infinite possibility of the void that lies just beyond the scrim of superficial consciousness. A participant in World War I and a witness to World War II, Fontana, like many 20th century

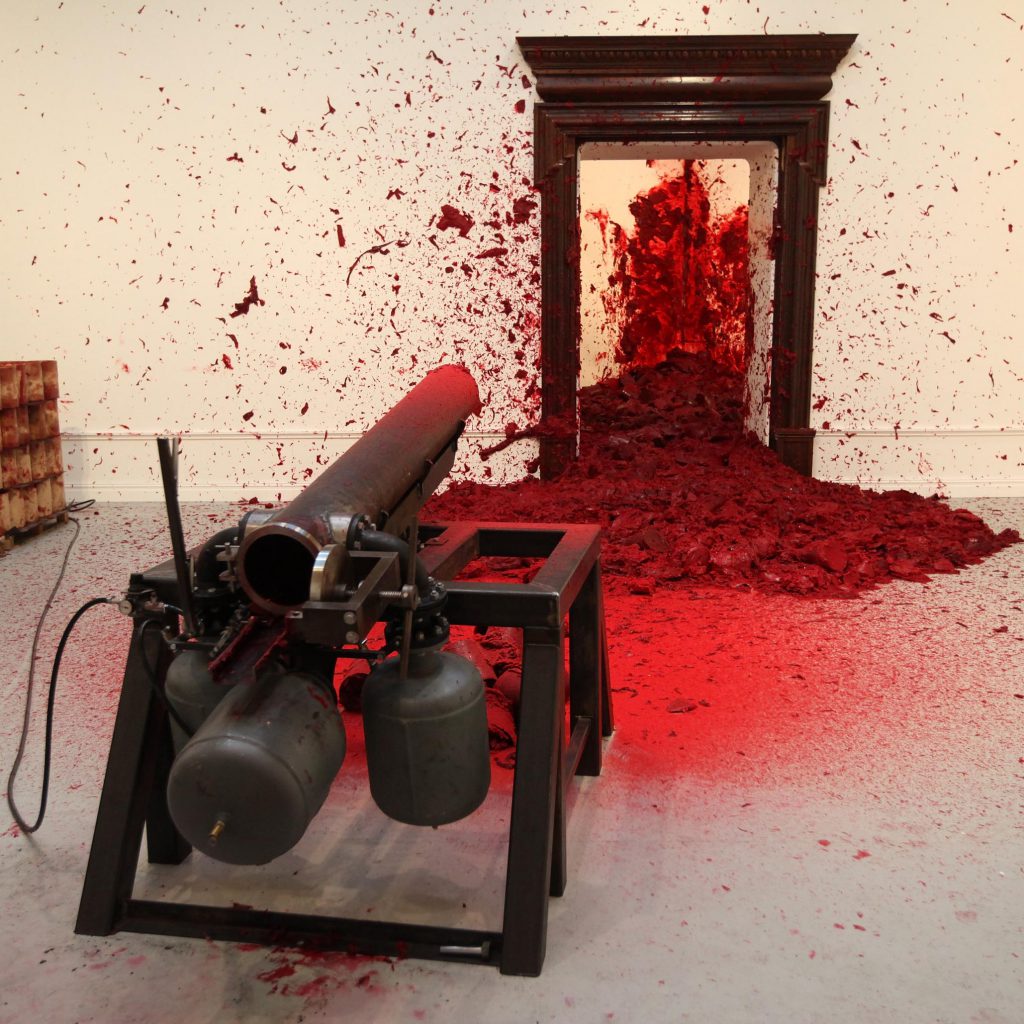

ANISH KAPOOR:

MY RED HOMELAND (2003), PAST PRESENT FUTURE (2006), SHOOTING INTO THE CORNER (2008/2009) AND RECENT PAINTINGS

Before Anish Kapoor pissed off every MFA recipient in the world with his “blackest black” monopoly (which is by now a controversy duller than the taupest taupe), he was packing his sculptures so full of pigments that it is difficult to believe he didn’t succumb to a technicolor version of coal workers’ pneumoconiosis.

ANA MENDIETA: SILUETA SANGRIENTA (1975) (AND OTHER WORKS FROM THE SILUETA SERIES THAT ARE PREDOMINANTLY RED)

Ana Mendieta wasn’t afraid of a little blood. Nor was she afraid to make something bleed. Born in Cuba but exiled to the United States at twelve due to her father’s anti-Castro activities, Mendieta came of age when land, performance, and conceptual art movements, as well as second-wave feminism, prevailed in the Western cultural ethos. They were important influences for her, though she would never align herself to any single movement or categorical practice.

YAYOI KUSAMA: HER DOTS, AND HER RED WIG

MARK ROTHKO: LIGHT RED OVER BLACK (1957) AND RED ON MAROON (1958)

One would hardly know that Mark Rothko sought to address the major philosophical issues of his time from the titles of his paintings alone. For example, Light Red Over Black offers little more than a general description of a 1957 piece. Red on Maroon, the title for a 1958 painting, is also banal. But Rothko was a serious man with a probing mind — the nature of spirituality in modern times was one theme that drove his creative explorations.

CHIHARU SHIOTA:

THE KEY IN THE HAND (2015), UNCERTAIN JOURNEY (2016/2019), AND DRIFTING (2019)

Chiharu Shiota is a master of the symbolic network; everything in her artwork is itself and something else. The boats, keys, and string in her watershed installation The Key in the Hand (2015), which she created for the Japanese Pavilion at the 56th Venice Biennale, represent open hands, ample opportunities, and the interconnectedness of existence, respectively.

In other works, the boats double as a metaphor for the journey of life, and the string, especially when red, becomes a neurological map or, more abstractly, the web of fate. Her recent projects, such as Uncertain Journey (shown at Blain | Southern, Berlin in 2016 and again as part of her solo exhibition The Soul Trembles at the Mori Art Museum, Tokyo in 2019) and Drifting (presented in Line of Thought at the Museum Sinclair-Haus, Bad Homburg, Germany in 2019), up the ante on how much elaboration these motifs can withstand, as whole environments are built out of taut and tangled yarn that seems to explode within the gallery. Shiota’s background in painting and performance art — she studied with Marina Abramović in the late 1990s — inform the spectacle, or what some call the theatricality, of her work, though the results are never melodramatic; rather, her visions are anchored by a clear understanding of what it means to be a person.